diff --git a/_quarto-en.yml b/_quarto-en.yml

index 9a3f433ba3..e86cefad20 100644

--- a/_quarto-en.yml

+++ b/_quarto-en.yml

@@ -20,6 +20,8 @@ project:

- content/modelisation/index.qmd

- content/modelisation/0_preprocessing.qmd

- content/modelisation/1_modelevaluation.qmd

+ - content/modelisation/2_classification.qmd

+ - content/modelisation/3_regression.qmd

website:

diff --git a/content/modelisation/2_classification.qmd b/content/modelisation/2_classification.qmd

index 34be041697..1ee72f2d17 100644

--- a/content/modelisation/2_classification.qmd

+++ b/content/modelisation/2_classification.qmd

@@ -1,16 +1,12 @@

---

title: "Découverte de la classification avec la technique des SVM"

+title-en: "Discovering classification with the SVM technique"

categories:

- Modélisation

description: |

- La classification permet d'attribuer une classe d'appartenance (_label_

- dans la terminologie du _machine learning_)

- discrète à des données à partir de certaines variables explicatives

- (_features_ dans la même terminologie).

- Les algorithmes de classification sont nombreux. L'un des plus intuitifs et

- les plus fréquemment rencontrés sont les _SVM_ (*Support Vector Machine*).

- Ce chapitre illustre les enjeux de la classification à partir de

- ce modèle sur les données de vote aux élections présidentielles US de 2020.

+ La classification permet d'attribuer une classe d'appartenance (_label_ dans la terminologie du _machine learning_) discrète à des données à partir de certaines variables explicatives (_features_ dans la même terminologie). Les algorithmes de classification sont nombreux. L'un des plus intuitifs et les plus fréquemment rencontrés sont les _SVM_ (*Support Vector Machine*). Ce chapitre illustre les enjeux de la classification à partir de ce modèle sur les données de vote aux élections présidentielles US de 2020.

+description-en: |

+ Classification enables us to assign a discrete membership class (_label_ in machine learning terminology) to data, based on certain explanatory variables (_features_ in the same terminology). Classification algorithms are numerous. One of the most intuitive and frequently encountered is _SVM_ (*Support Vector Machine*). This chapter illustrates the challenges of using this model to classify model on voting data for the 2020 US presidential elections.

echo: false

---

@@ -19,21 +15,31 @@ echo: false

printMessage="true"

>}}

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

# Introduction

-Ce chapitre vise à présenter de manière très succincte le principe de l'entraînement de modèles dans un cadre de classification. L'objectif est d'illustrer la démarche à partir d'un algorithme dont le principe est assez intuitif. Il s'agit d'illustrer quelques uns des concepts évoqués dans les chapitres précédents, notamment ceux relatifs à l'entraînement d'un modèle. D'autres cours de votre scolarité vous permettront de découvrir d'autres algorithmes de classification et les limites de chaque technique.

-

+Ce chapitre vise à présenter de manière très succincte le principe de l'entraînement de modèles dans un cadre de classification. L'objectif est d'illustrer la démarche à partir d'un algorithme dont le principe est assez intuitif. Il s'agit d'illustrer quelques uns des concepts évoqués dans les chapitres précédents, notamment ceux relatifs à l'entraînement d'un modèle. D'autres cours de votre scolarité vous permettront de découvrir d'autres algorithmes de classification et les limites de chaque technique.

## Données

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+# Introduction

+

+This chapter aims to very briefly introduce the principle of training models in a classification context. The goal is to illustrate the process using an algorithm with an intuitive principle. It seeks to demonstrate some of the concepts discussed in previous chapters, particularly those related to model training. Other courses in your curriculum will allow you to explore additional classification algorithms and the limitations of each technique.

+

+## Data

+:::

{{< include _import_data_ml.qmd >}}

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

## La méthode des _SVM_ (_Support Vector Machines_)

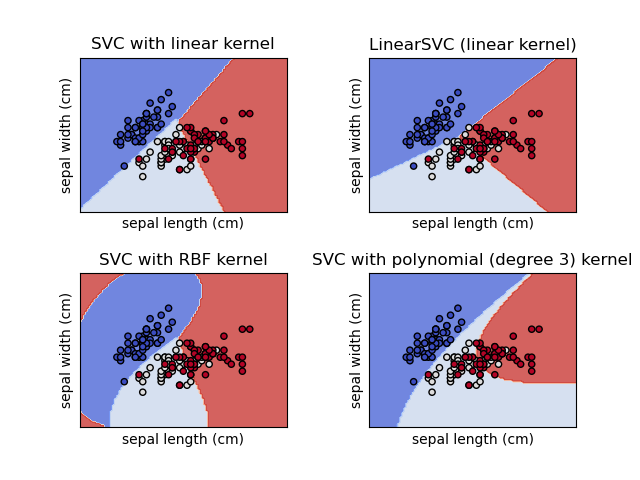

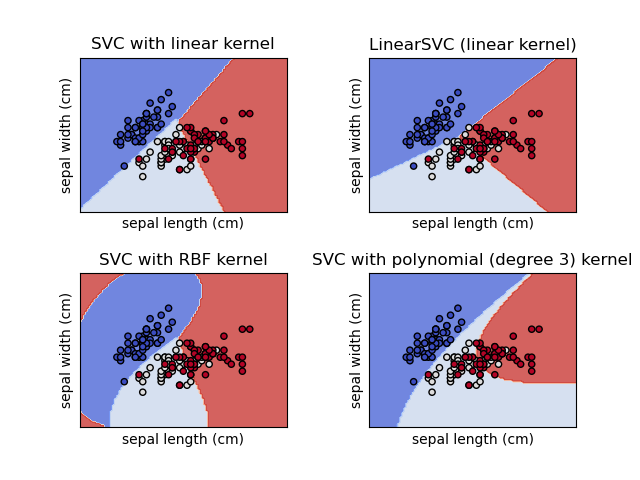

Les SVM (_Support Vector Machines_) font partie de la boîte à outil traditionnelle des _data scientists_.

Le principe de cette technique est relativement intuitif grâce à son interprétation géométrique.

-Il s'agit de trouver une droite, avec des marges (les supports) qui discrimine au mieux le nuage de point de nos données.

+Il s'agit de trouver une droite, avec des marges (les supports) qui discrimine au mieux le nuage de points de nos données.

Bien-sûr, dans la vraie vie, il est rare d'avoir des nuages de points bien ordonnés pour pouvoir les séparer par une droite. Mais une projection adéquate (un noyau ou _kernel_) peut arranger des données pour permettre de discriminer les données.

```{=html}

@@ -61,12 +67,52 @@ des _labels_ homogènes.

On peut, sans perdre de généralité,

supposer que le problème consiste à supposer l'existence d'une loi de probabilité $\mathbb{P}(x,y)$ ($\mathbb{P} \to \{-1,1\}$) qui est inconnue. Le problème de discrimination

vise à construire un estimateur de la fonction de décision idéale qui minimise la probabilité d'erreur. Autrement dit

+:::

+

+::::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+## The SVM Method (_Support Vector Machines_)

+

+SVM (_Support Vector Machines_) is part of the traditional toolkit for _data scientists_.

+The principle of this technique is relatively intuitive thanks to its geometric interpretation.

+The goal is to find a line, with margins (supports), that best separates the point cloud in our data.

+Of course, in real life, it is rare to have well-organized point clouds that can be separated by a line. However, an appropriate projection (a kernel) can transform the data to enable separation.

+

+```{=html}

+ +```

+

+::: {.tip}

+## Mathematical formalization

+

+SVM is one of the most intuitive _machine learning_ methods

+due to its simple geometric interpretation. It is also

+one of the least complex _machine learning_ algorithms in terms of formalization

+for practitioners familiar with traditional statistics. This note provides an overview, though it is not essential for understanding this chapter.

+In _machine learning_, more than the mathematical details, the key is to build intuitions.

+

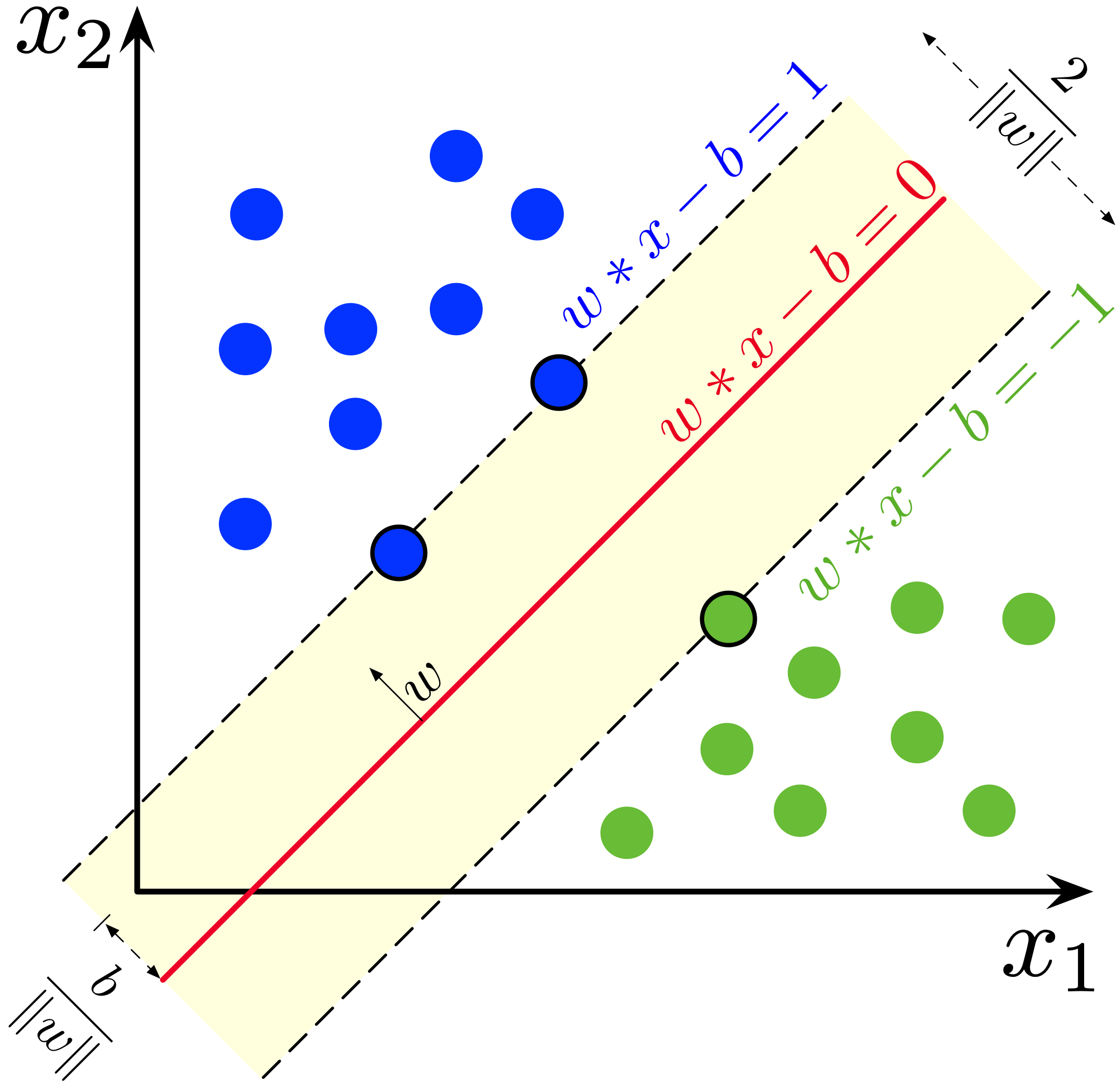

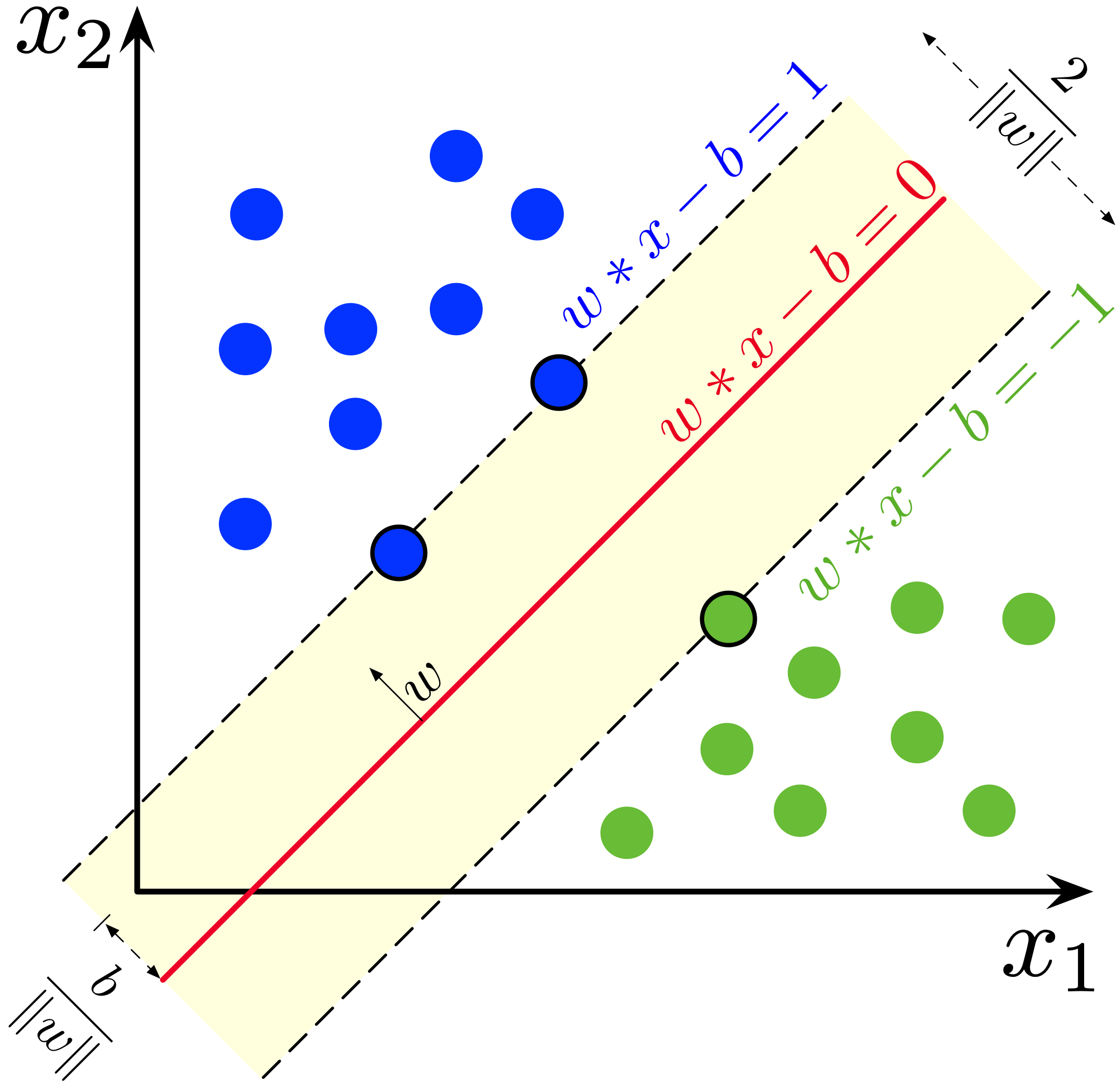

+The goal of SVM, let us recall, is to find a hyperplane that

+best separates the different classes. For example, in a two-dimensional space,

+it aims to find a line with margins that best divides the space into regions

+with homogeneous _labels_.

+

+Without loss of generality, we can assume the problem involves a probability distribution $\mathbb{P}(x,y)$ ($\mathbb{P} \to \{-1,1\}$) that is unknown. The goal of classification is to build an estimator of the ideal decision function that minimizes the probability of error. In other words

+:::

+

$$

\theta = \arg\min_\Theta \mathbb{P}(h_\theta(X) \neq y |x)

$$

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

Les SVM les plus simples sont les SVM linéaires. Dans ce cas, on suppose qu'il existe un séparateur linéaire qui permet d'associer chaque classe à son signe:

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+The simplest SVMs are linear SVMs. In this case, it is assumed that a linear separator exists that can assign each class based on its sign:

+:::

+

$$

h_\theta(x) = \text{signe}(f_\theta(x)) ; \text{ avec } f_\theta(x) = \theta^T x + b

@@ -77,20 +123,34 @@ avec $\theta \in \mathbb{R}^p$ et $w \in \mathbb{R}$.

+```

+

+::: {.tip}

+## Mathematical formalization

+

+SVM is one of the most intuitive _machine learning_ methods

+due to its simple geometric interpretation. It is also

+one of the least complex _machine learning_ algorithms in terms of formalization

+for practitioners familiar with traditional statistics. This note provides an overview, though it is not essential for understanding this chapter.

+In _machine learning_, more than the mathematical details, the key is to build intuitions.

+

+The goal of SVM, let us recall, is to find a hyperplane that

+best separates the different classes. For example, in a two-dimensional space,

+it aims to find a line with margins that best divides the space into regions

+with homogeneous _labels_.

+

+Without loss of generality, we can assume the problem involves a probability distribution $\mathbb{P}(x,y)$ ($\mathbb{P} \to \{-1,1\}$) that is unknown. The goal of classification is to build an estimator of the ideal decision function that minimizes the probability of error. In other words

+:::

+

$$

\theta = \arg\min_\Theta \mathbb{P}(h_\theta(X) \neq y |x)

$$

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

Les SVM les plus simples sont les SVM linéaires. Dans ce cas, on suppose qu'il existe un séparateur linéaire qui permet d'associer chaque classe à son signe:

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+The simplest SVMs are linear SVMs. In this case, it is assumed that a linear separator exists that can assign each class based on its sign:

+:::

+

$$

h_\theta(x) = \text{signe}(f_\theta(x)) ; \text{ avec } f_\theta(x) = \theta^T x + b

@@ -77,20 +123,34 @@ avec $\theta \in \mathbb{R}^p$ et $w \in \mathbb{R}$.

```

-Lorsque des observations sont linéairement séparables,

-il existe une infinité de frontières de décision linéaire séparant les deux classes. Le _"meilleur"_ choix est de prendre la marge maximale permettant de séparer les données. La distance entre les deux marges est $\frac{2}{||\theta||}$. Donc maximiser cette distance entre deux hyperplans revient à minimiser $||\theta||^2$ sous la contrainte $y_i(\theta^Tx_i + b) \geq 1$.

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+Lorsque des observations sont linéairement séparables, il existe une infinité de frontières de décision linéaire séparant les deux classes. Le _"meilleur"_ choix est de prendre la marge maximale permettant de séparer les données. La distance entre les deux marges est $\frac{2}{||\theta||}$. Donc maximiser cette distance entre deux hyperplans revient à minimiser $||\theta||^2$ sous la contrainte $y_i(\theta^Tx_i + b) \geq 1$.

Dans le cas non linéairement séparable, la *hinge loss* $\max\big(0,y_i(\theta^Tx_i + b)\big)$ permet de linéariser la fonction de perte, ce qui donne le programme d'optimisation suivant :

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+When observations are linearly separable, there is an infinite number of linear decision boundaries separating the two classes. The _"best"_ choice is to select the maximum margin that separates the data. The distance between the two margins is $\frac{2}{||\theta||}$. Thus, maximizing this distance between two hyperplanes is equivalent to minimizing $||\theta||^2$ under the constraint $y_i(\theta^Tx_i + b) \geq 1$.

+

+In the non-linearly separable case, the *hinge loss* $\max\big(0,y_i(\theta^Tx_i + b)\big)$ allows for linearizing the loss function, resulting in the following optimization problem:

+:::

$$

\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \max\big(0,y_i(\theta^Tx_i + b)\big) + \lambda ||\theta||^2

$$

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

La généralisation au cas non linéaire implique d'introduire des noyaux transformant l'espace de coordonnées des observations.

+:::

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+Generalization to the non-linear case involves introducing kernels that transform the coordinate space of the observations.

:::

+::::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

# Application

Pour appliquer un modèle de classification, il nous faut

@@ -101,6 +161,16 @@ défaite d'un des partis.

Même si les Républicains ont perdu en 2020, ils l'ont emporté

dans plus de comtés (moins peuplés). Nous allons considérer

que la victoire des Républicains est notre _label_ 1 et la défaite _0_.

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+# Application

+

+To apply a classification model, we need to find a dichotomous variable. The natural choice is to use the dichotomous variable of a party's victory or defeat.

+

+Even though the Republicans lost in 2020, they won in more counties (less populated ones). We will consider a Republican victory as our _label_ 1 and a defeat as _0_.

+:::

+

```{python}

#| echo: true

@@ -111,7 +181,10 @@ from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

```

-::: {.exercise}

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+

+:::: {.exercise}

## Exercice 1 : Premier algorithme de classification

1. Créer une variable *dummy* appelée `y` dont la valeur vaut 1 quand les républicains l'emportent.

@@ -133,7 +206,48 @@ créer des échantillons de test (20 % des observations) et d'estimation (80 %)

6. Changer de variables *x*. Utiliser uniquement le résultat passé du vote démocrate (année 2016) et le revenu. Les variables en question sont `share_2016_republican` et `Median_Household_Income_2019`. Regarder les résultats, notamment la matrice de confusion.

7. [OPTIONNEL] Faire une 5-fold validation croisée pour déterminer le paramètre *C* idéal.

+::::

+

+:::

+

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+::: {.exercise}

+

+## Exercise 1: First classification algorithm

+

+1. Create a *dummy* variable called `y` with a value of 1 when the Republicans win.

+2. Using the ready-to-use function `train_test_split` from the `sklearn.model_selection` library,

+create test samples (20% of the observations) and training samples (80%) with the following *features*:

+

+```python

+vars = [

+ "Unemployment_rate_2019", "Median_Household_Income_2019",

+ "Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19",

+ "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"

+]

+```

+

+and use the variable `y` as the *label*.

+

+*Note: You may encounter the following warning:*

+

+> A column-vector y was passed when a 1d array was expected. Please change the shape of y to (n_samples, ), for example using ravel()

+

+*Note: To avoid this warning every time you train your model, you can use `DataFrame[['y']].values.ravel()` instead of `DataFrame[['y']]` when preparing your samples.*

+

+3. Train an SVM classifier with a regularization parameter `C = 1`. Examine the following performance metrics: `accuracy`, `f1`, `recall`, and `precision`.

+

+4. Check the confusion matrix: despite seemingly reasonable scores, you should notice a significant issue.

+

+5. Repeat the previous steps using normalized variables. Are the results different?

+

+6. Change the *x* variables. Use only the previous Democratic vote result (2016) and income. The variables in question are `share_2016_republican` and `Median_Household_Income_2019`. Examine the results, particularly the confusion matrix.

+

+7. [OPTIONAL] Perform 5-fold cross-validation to determine the ideal *C* parameter.

+

:::

+::::

```{python}

@@ -144,7 +258,11 @@ votes['y'] = (votes['votes_gop'] > votes['votes_dem']).astype(int)

```{python}

#2. Création des échantillons d'entraînement et de validation

-xvars = ['Unemployment_rate_2019', 'Median_Household_Income_2019', 'Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19', "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"]

+xvars = [

+ 'Unemployment_rate_2019', 'Median_Household_Income_2019',

+ 'Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19',

+ "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"

+]

df = votes.loc[:, ["y"] + xvars]

@@ -154,13 +272,25 @@ X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

)

```

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

On obtient donc un ensemble de _features_ d'entraînement ayant cette forme:

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+We thus obtain a set of training _features_ with the following structure:

+:::

```{python}

X_train.head()

```

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

Et les _labels_ associés sont les suivants:

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+And the associated _labels_ are as follows:

+:::

```{python}

y_test

@@ -179,11 +309,22 @@ sc_precision = sklearn.metrics.precision_score(y_pred, y_test)

```

```{python}

-stats_perf = pd.DataFrame.from_dict({"Accuracy": [sc_accuracy], "Recall": [sc_recall],

- "Precision": [sc_precision], "F1": [sc_f1]}, orient = "index", columns = ["Score"])

+stats_perf = pd.DataFrame.from_dict(

+ {

+ "Accuracy": [sc_accuracy], "Recall": [sc_recall],

+ "Precision": [sc_precision], "F1": [sc_f1]

+ }, orient = "index", columns = ["Score"]

+)

```

-A l'issue de la question 3, notre classifieur manque totalement les labels 0, qui sont minoritaires. Parmi les raisons possibles: l'échelle des variables. Le revenu, notamment, a une distribution qui peut écraser celle des autres variables, dans un modèle linéaire. Il faut donc, a minima, standardiser les variables, ce qui est l'objet de la question 4

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+A l'issue de la question 3, notre classifieur manque totalement les labels 0, qui sont minoritaires. Parmi les raisons possibles : l'échelle des variables. Le revenu, notamment, a une distribution qui peut écraser celle des autres variables, dans un modèle linéaire. Il faut donc, a minima, standardiser les variables, ce qui est l'objet de la question 4.

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+At the end of question 3, our classifier completely misses the 0 labels, which are in the minority. One possible reason is the scale of the variables. Income, in particular, has a distribution that can dominate the others in a linear model. Therefore, at a minimum, it is necessary to standardize the variables, which is the focus of question 4.

+:::

@@ -201,15 +342,21 @@ disp.plot()

plt.show()

```

-Standardiser les variables n'apporte finalement pas de gain:

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+Standardiser les variables n'apporte finalement pas de gain :

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+Standardizing the variables ultimately does not bring any improvement:

+:::

```{python}

import sklearn.preprocessing as preprocessing

X = df.loc[:, xvars]

y = df[['y']]

-scaler = preprocessing.StandardScaler().fit(X) #Ici on estime

-X = scaler.transform(X) #Ici on standardise

+scaler = preprocessing.StandardScaler().fit(X)

+X = scaler.transform(X)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X,

@@ -220,30 +367,39 @@ clf = svm.SVC(kernel='linear', C=1).fit(X_train, y_train)

predictions = clf.predict(X_test)

cm = sklearn.metrics.confusion_matrix(y_test, predictions, labels=clf.classes_)

disp = sklearn.metrics.ConfusionMatrixDisplay(

- confusion_matrix=cm,

- display_labels=clf.classes_

- )

+ confusion_matrix=cm,

+ display_labels=clf.classes_

+)

disp.plot()

plt.show()

```

-Il faut donc aller plus loin : le problème ne vient pas de l'échelle mais du choix des variables. C'est pour cette raison que l'étape de sélection de variable est cruciale et qu'un chapitre y est consacré.

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+Il faut donc aller plus loin : le problème ne vient pas de l'échelle mais du choix des variables. C'est pour cette raison que l'étape de sélection de variables est cruciale et qu'un chapitre y est consacré.

-A l'issue de la question 6,

-le nouveau classifieur avec devrait avoir les performances suivantes :

+À l'issue de la question 6, le nouveau classifieur devrait avoir les performances suivantes :

+:::

-```{python}

-#| output: asis

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+It is therefore necessary to go further: the problem does not lie in the scale but in the choice of variables. This is why the step of variable selection is crucial and why a chapter is dedicated to it.

-out = pd.DataFrame.from_dict({"Accuracy": [sc_accuracy], "Recall": [sc_recall],

- "Precision": [sc_precision], "F1": [sc_f1]}, orient = "index", columns = ["Score"])

-```

+At the end of question 6, the new classifier should have the following performance:

+:::

+```{python}

+#| output: asis

+out = pd.DataFrame.from_dict(

+ {

+ "Accuracy": [sc_accuracy], "Recall": [sc_recall],

+ "Precision": [sc_precision], "F1": [sc_f1]

+ }, orient = "index", columns = ["Score"]

+)

+```

```{python}

-# 6. Refaire les questions en changeant la variable X.

+# Question 6

votes['y'] = (votes['votes_gop'] > votes['votes_dem']).astype(int)

df = votes[["y", "share_2016_republican", 'Median_Household_Income_2019']]

tempdf = df.dropna(how = "any")

@@ -266,11 +422,6 @@ sc_f1 = sklearn.metrics.f1_score(y_pred, y_test)

sc_recall = sklearn.metrics.recall_score(y_pred, y_test)

sc_precision = sklearn.metrics.precision_score(y_pred, y_test)

-#print(sc_accuracy)

-#print(sc_f1)

-#print(sc_recall)

-#print(sc_precision)

-

predictions = clf.predict(X_test)

cm = sklearn.metrics.confusion_matrix(y_test, predictions, labels=clf.classes_)

disp = sklearn.metrics.ConfusionMatrixDisplay(

@@ -278,7 +429,6 @@ disp = sklearn.metrics.ConfusionMatrixDisplay(

display_labels=clf.classes_

)

disp.plot()

-# On obtient un résultat beaucoup plus cohérent.

plt.savefig("confusion_matrix3.png")

```

diff --git a/content/modelisation/3_regression.qmd b/content/modelisation/3_regression.qmd

index ceaada2199..21ffc2f2de 100644

--- a/content/modelisation/3_regression.qmd

+++ b/content/modelisation/3_regression.qmd

@@ -1,14 +1,12 @@

---

title: "Introduction à la régression"

+title-en: "An introduction to regression"

categories:

- Modélisation

description: |

- La régression linéaire est la première modélisation statistique

- qu'on découvre dans un cursus quantitatif. Il s'agit en effet d'une

- méthode très intuitive et très riche. Le _Machine Learning_ permet de

- l'appréhender d'une autre manière que l'économétrie. Avec `scikit` et

- `statsmodels`, on dispose de tous les outils pour satisfaire à la fois

- data scientists et économistes.

+ La régression linéaire est la première modélisation statistique qu'on découvre dans un cursus quantitatif. Il s'agit en effet d'une méthode très intuitive et très riche. Le _Machine Learning_ permet de l'appréhender d'une autre manière que l'économétrie. Avec `scikit` et `statsmodels`, on dispose de tous les outils pour satisfaire à la fois data scientists et économistes.

+description-en: |

+ Linear regression is the first statistical modeling to be discovered in a quantitative curriculum. It is a very intuitive and rich method. Machine Learning allows us to approach it in a different way to econometrics. With `scikit` and `statsmodels`, we have all the tools we need to satisfy both data scientists and economists.

image: featured_regression.png

echo: false

bibliography: ../../reference.bib

@@ -19,6 +17,7 @@ bibliography: ../../reference.bib

>}}

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

Le précédent chapitre visait à proposer un premier modèle pour comprendre

les comtés où le parti Républicain l'emporte. La variable d'intérêt étant

bimodale (victoire ou défaite), on était dans le cadre d'un modèle de

@@ -28,13 +27,29 @@ Maintenant, sur les mêmes données, on va proposer un modèle de régression

pour expliquer le score du parti Républicain. La variable est donc continue.

Nous ignorerons le fait que ses bornes se trouvent entre 0 et 100 et donc

qu'il faudrait, pour être rigoureux, transformer l'échelle afin d'avoir

-des données dans cet intervalle.

+des données dans cet intervalle.

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+The previous chapter aimed to propose a first model to understand the counties where the Republican Party wins. The variable of interest was bimodal (win or lose), placing us within the framework of a classification model.

+

+Now, using the same data, we will propose a regression model to explain the Republican Party's score. The variable is thus continuous. We will ignore the fact that its bounds lie between 0 and 100, meaning that to be rigorous, we would need to transform the scale so that the data fits within this interval.

+:::

+

{{< include _import_data_ml.qmd >}}

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

Ce chapitre va utiliser plusieurs _packages_

de modélisation, les principaux étant `Scikit` et `Statsmodels`.

Voici une suggestion d'import pour tous ces _packages_.

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+This chapter will use several modeling _packages_, the main ones being `Scikit` and `Statsmodels`.

+Here is a suggested import for all these _packages_.

+:::

+

```{python}

#| echo: true

@@ -48,6 +63,7 @@ import pandas as pd

```

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

# Principe général

Le principe général de la régression consiste à trouver une loi $h_\theta(X)$

@@ -56,15 +72,35 @@ telle que

$$

h_\theta(X) = \mathbb{E}_\theta(Y|X)

$$

+

Cette formalisation est extrêmement généraliste et ne se restreint d'ailleurs

-par à la régression linéaire.

+pas à la régression linéaire.

En économétrie, la régression offre une alternative aux méthodes de maximum

de vraisemblance et aux méthodes des moments. La régression est un ensemble

très vaste de méthodes, selon la famille de modèles

-(paramétriques, non paramétriques, etc.) et la structure de modèles.

+(paramétriques, non paramétriques, etc.) et la structure de modèles.

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+# General Principle

+The general principle of regression consists of finding a law $h_\theta(X)$

+such that

+$$

+h_\theta(X) = \mathbb{E}_\theta(Y|X)

+$$

+

+This formalization is extremely general and is not limited to linear regression.

+

+In econometrics, regression offers an alternative to maximum likelihood methods

+and moment methods. Regression encompasses a very broad range of methods, depending on the family of models

+(parametric, non-parametric, etc.) and model structures.

+:::

+

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

## La régression linéaire

C'est la manière la plus simple de représenter la loi $h_\theta(X)$ comme

@@ -75,7 +111,6 @@ $$

\mathbb{E}_\theta(Y|X) = X\beta

$$

-

Cette relation est encore, sous cette formulation, théorique. Il convient

de l'estimer à partir des données observées $y$. La méthode des moindres

carrés consiste à minimiser l'erreur quadratique entre la prédiction et

@@ -83,45 +118,96 @@ les données observées (ce qui explique qu'on puisse voir la régression comme

un problème de *Machine Learning*). En toute généralité, la méthode des

moindres carrés consiste à trouver l'ensemble de paramètres $\theta$

tel que

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+## Linear Regression

+

+This is the simplest way to represent the law $h_\theta(X)$ as

+a linear combination of variables $X$ and parameters $\theta$. In this case,

+

+$$

+\mathbb{E}_\theta(Y|X) = X\beta

+$$

+

+This relationship is, under this formulation, theoretical. It must

+be estimated from the observed data $y$. The method of least squares aims to minimize

+the quadratic error between the prediction and the observed data (which explains

+why regression can be seen as a *Machine Learning* problem). In general, the method of

+least squares seeks to find the set of parameters $\theta$ such that

+:::

$$

\theta = \arg \min_{\theta \in \Theta} \mathbb{E}\bigg[ \left( y - h_\theta(X) \right)^2 \bigg]

$$

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

Ce qui, dans le cadre de la régression linéaire, s'exprime de la manière suivante :

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+Which, in the context of linear regression, is expressed as follows:

+:::

$$

\beta = \arg\min \mathbb{E}\bigg[ \left( y - X\beta \right)^2 \bigg]

$$

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

Lorsqu'on amène le modèle théorique ($\mathbb{E}_\theta(Y|X) = X\beta$) aux données,

on formalise le modèle de la manière suivante :

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+When the theoretical model ($\mathbb{E}_\theta(Y|X) = X\beta$) is applied to data,

+the model is formalized as follows:

+:::

$$

Y = X\beta + \epsilon

$$

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

Avec une certaine distribution du bruit $\epsilon$ qui dépend

des hypothèses faites. Par exemple, avec des

$\epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0,\sigma^2)$ i.i.d., l'estimateur $\beta$ obtenu

est équivalent à celui du Maximum de Vraisemblance dont la théorie asymptotique

nous assure l'absence de biais, la variance minimale (borne de Cramer-Rao).

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+With a certain distribution of the noise $\epsilon$ that depends

+on the assumptions made. For example, with

+$\epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0,\sigma^2)$ i.i.d., the estimator $\beta$ obtained

+is equivalent to the Maximum Likelihood Estimator, whose asymptotic theory

+ensures unbiasedness and minimum variance (Cramer-Rao bound).

+:::

### Application

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

Toujours sous le patronage des héritiers de @siegfried1913tableau, notre objectif, dans ce chapitre, est d'expliquer et prédire le score des Républicains à partir de quelques

variables socioéconomiques. Contrairement au chapitre précédent, où on se focalisait sur

un résultat binaire (victoire/défaite des Républicains), cette

fois on va chercher à modéliser directement le score des Républicains.

-

Le prochain exercice vise à illustrer la manière d'effectuer une régression linéaire avec `scikit`.

Dans ce domaine,

`statsmodels` est nettement plus complet, ce que montrera l'exercice suivant.

L'intérêt principal de faire

des régressions avec `scikit` est de pouvoir comparer les résultats d'une régression linéaire

avec d'autres modèles de régression dans une perspective de sélection du meilleur modèle prédictif.

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+Under the guidance of the heirs of @siegfried1913tableau, our objective in this chapter is to explain and predict the Republican score based on some socioeconomic variables. Unlike the previous chapter, where we focused on a binary outcome (Republican victory/defeat), this time we will model the Republican score directly.

+The next exercise aims to demonstrate how to perform linear regression using `scikit`.

+In this area, `statsmodels` is significantly more comprehensive, as the following exercise will demonstrate.

+The main advantage of performing regressions with `scikit` is the ability to compare the results of linear regression with other regression models in the context of selecting the best predictive model.

+:::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

::: {.exercise}

## Exercice 1a : Régression linéaire avec scikit

@@ -139,14 +225,37 @@ en `log` sinon son échelle risque d'écraser tout effet.

et des erreurs de prédiction. Observez-vous

un problème de spécification ?

+:::

+::::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+

+::: {.exercise}

+## Exercise 1a: Linear Regression with scikit

+

+1. Using a few variables, for example, *'Unemployment_rate_2019', 'Median_Household_Income_2019', 'Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19', "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"*, explain the variable `per_gop` using a training sample `X_train` prepared beforehand.

+

+⚠️ Use the variable `Median_Household_Income_2019` in `log` form; otherwise, its scale might dominate and obscure other effects.

+

+2. Display the values of the coefficients, including the constant.

+

+3. Evaluate the relevance of the model using $R^2$ and assess the fit quality with the MSE.

+

+4. Plot a scatter plot of observed values and prediction errors. Do you observe any specification issues?

:::

+::::

+

```{python}

#| output: false

-# 1. Régression linéaire de per_gop sur différentes variables explicatives

-xvars = ['Unemployment_rate_2019', 'Median_Household_Income_2019', 'Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19', "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"]

+# Question 1

+xvars = [

+ 'Unemployment_rate_2019', 'Median_Household_Income_2019',

+ 'Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19',

+ "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"

+]

df2 = votes[["per_gop"] + xvars].copy()

df2['log_income'] = np.log(df2["Median_Household_Income_2019"])

@@ -160,7 +269,6 @@ X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

ols = LinearRegression().fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred = ols.predict(X_test)

-#y_pred[:10]

```

@@ -168,7 +276,7 @@ y_pred = ols.predict(X_test)

```{python}

#| output: false

-#2. Afficher les valeurs des coefficients

+# Question 2

print(ols.intercept_, ols.coef_)

```

@@ -176,48 +284,56 @@ print(ols.intercept_, ols.coef_)

```{python}

#| output: false

-# 3. Evaluer la pertinence du modèle

+# Question 3

rmse = sklearn.metrics.mean_squared_error(y_test, y_pred, squared = False)

rsq = sklearn.metrics.r2_score(y_test, y_pred)

-print('Mean squared error: %.2f'

- % rmse)

-# The coefficient of determination: 1 is perfect prediction

-print('Coefficient of determination: %.2f'

- % rsq)

+print(

+ f'Mean squared error: {rmse:.2f}'

+)

+

+print(

+ f'Coefficient of determination: {rsq.2f}'

+)

```

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+À la question 4, on peut voir que la répartition des erreurs n'est clairement pas aléatoire en fonction de $X$.

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+In question 4, it can be observed that the distribution of errors is clearly not random with respect to $X$.

+:::

+

+

```{python}

#| output: false

#4. Nuage de points des valeurs observées

-tempdf = pd.DataFrame({"prediction": y_pred, "observed": y_test,

- "error": y_test - y_pred})

+tempdf = pd.DataFrame(

+ {

+ "prediction": y_pred, "observed": y_test,

+ "error": y_test - y_pred

+ }

+)

fig = plt.figure()

g = sns.scatterplot(data = tempdf, x = "observed", y = "error")

g.axhline(0, color = "red")

-

-# La répartition des erreurs n'est clairement pas

-# aléatoire en fonction de $X$.

-# Le modèle souffre

-# donc d'un problème de spécification.

```

-Voici le nuage de points de nos erreurs:

-

```{python}

g.figure.get_figure()

```

-```{python}

-#| output: false

-g.figure.get_figure().savefig("featured_regression.png")

-```

-

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+Le modèle souffre donc d'un problème de spécification, il faudra par la suite faire un travail sur les variables sélectionnées. Avant cela, on peut refaire cet exercice avec le _package_ `statsmodels`.

+:::

-Clairement, le modèle présente un problème de spécification.

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+The model therefore suffers from a specification issue, so work will need to be done on the selected variables later. Before that, we can redo this exercise using the `statsmodels` package.

+:::

```{python}

@@ -226,6 +342,8 @@ import statsmodels.api as sm

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

```

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+

::: {.exercise}

## Exercice 1b : Régression linéaire avec statsmodels

@@ -245,15 +363,41 @@ en `log` sinon son échelle risque d'écraser tout effet.

:::

+::::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+

+::: {.exercise}

+## Exercise 1b: Linear Regression with statsmodels

+

+This exercise aims to demonstrate how to perform linear regression using `statsmodels`, which offers features more similar to those of `R` and less oriented toward *Machine Learning*.

+

+The goal is still to explain the Republican score based on a few variables.

+

+1. Using a few variables, for example, *'Unemployment_rate_2019', 'Median_Household_Income_2019', 'Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19', "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"*, explain the variable `per_gop`.

+⚠️ Use the variable `Median_Household_Income_2019` in `log` form; otherwise, its scale might dominate and obscure other effects.

+

+2. Display a regression table.

+

+3. Evaluate the model's relevance using the R^2.

+

+4. Use the `formula` API to regress the Republican score as a function of the variable `Unemployment_rate_2019`, `Unemployment_rate_2019` squared, and the log of `Median_Household_Income_2019`.

+:::

+

+::::

+

+

```{python}

#| output: false

-# 1. Régression linéaire de per_gop sur différentes variables explicatives

-xvars = ['Unemployment_rate_2019', 'Median_Household_Income_2019', 'Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19', "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"]

-

-xvars = ['Unemployment_rate_2019', 'Median_Household_Income_2019', 'Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19', "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"]

+# Question 1

+xvars = [

+ 'Unemployment_rate_2019', 'Median_Household_Income_2019',

+ 'Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19',

+ "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"

+]

-df2 = votes[["per_gop"] + xvars].copy()

+df2 = votes.loc[:, ["per_gop"] + xvars].copy()

df2['log_income'] = np.log(df2["Median_Household_Income_2019"])

df2 = df2.dropna().astype(np.float64)

@@ -262,19 +406,15 @@ results = sm.OLS(df2[['per_gop']], X).fit()

```

-

```{python}

#| output: false

-# 2. Afficher le tableau de régression

+# Question 2

print(results.summary())

-# html_snippet = results.summary().as_html()

```

```{python}

-#| output: false

-

# 3. Calcul du R^2

print("R2: ", results.rsquared)

```

@@ -289,6 +429,8 @@ results = smf.ols('per_gop ~ Unemployment_rate_2019 + I(Unemployment_rate_2019**

print(results.summary())

```

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+

::: {.tip}

Pour sortir une belle table pour un rapport sous $\LaTeX$, il est possible d'utiliser

@@ -313,16 +455,44 @@ englober ces modèles.

:::

+::::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+

+::: {.tip}

+To generate a well-formatted table for a report in $\LaTeX$, you can use the method [`Summary.as_latex`](https://www.statsmodels.org/devel/generated/statsmodels.iolib.summary.Summary.as_latex.html#statsmodels.iolib.summary.Summary.as_latex). For an HTML report, you can use [`Summary.as_html`](https://www.statsmodels.org/devel/generated/statsmodels.iolib.summary.Summary.as_latex.html#statsmodels.iolib.summary.Summary.as_latex).

+:::

+

+::: {.note}

+Users of `R` will find many familiar features in `statsmodels`, particularly the ability to use a formula to define a regression. The philosophy of `statsmodels` is similar to that which influenced the construction of `R`'s `stats` and `MASS` packages: providing a general-purpose library with a wide range of models.

+

+However, `statsmodels` benefits from being more modern compared to `R`'s packages. Since the 1990s, `R` packages aiming to provide missing features in `stats` and `MASS` have proliferated, while `statsmodels`, born in the 2010s, only had to propose a general framework (the *generalized estimating equations*) to encompass these models.

+:::

+

+

+::::

+

## La régression logistique

-Ce modèle s'applique à une distribution binaire.

-Dans ce cas, $\mathbb{E}_{\theta} (Y|X) = \mathbb{P}_{\theta} (Y = 1|X)$.

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+Nous avons appliqué notre régression linéaire sur une variable d'_outcome_ continue.

+Comment faire avec une distribution binaire ?

+Dans ce cas, $\mathbb{E}_{\theta} (Y|X) = \mathbb{P}_{\theta} (Y = 1|X)$.

La régression logistique peut être vue comme un modèle linéaire en probabilité :

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+We applied our linear regression to a continuous _outcome_ variable.

+How do we handle a binary distribution?

+In this case, $\mathbb{E}_{\theta} (Y|X) = \mathbb{P}_{\theta} (Y = 1|X)$.

+Logistic regression can be seen as a linear probability model:

+:::

$$

\text{logit}\bigg(\mathbb{E}_{\theta}(Y|X)\bigg) = \text{logit}\bigg(\mathbb{P}_{\theta}(Y = 1|X)\bigg) = X\beta

$$

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

La fonction $\text{logit}$ est $]0,1[ \to \mathbb{R}: p \mapsto \log(\frac{p}{1-p})$.

Elle permet ainsi de transformer une probabilité dans $\mathbb{R}$.

@@ -337,11 +507,35 @@ manières différentes :

l'outcome. Par exemple, si on observe les choix de participer ou non au marché

du travail, on va modéliser les facteurs déterminant ce choix ;

* En *Machine Learning*, le modèle latent n'est nécessaire que pour classifier

-dans la bonne catégorie les observations

+dans la bonne catégorie les observations.

L'estimation des paramètres $\beta$ peut se faire par maximum de vraisemblance

ou par régression, les deux solutions sont équivalentes sous certaines

-hypothèses.

+hypothèses.

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+The $\text{logit}$ function is $]0,1[ \to \mathbb{R}: p \mapsto \log(\frac{p}{1-p})$.

+

+It allows a probability to be transformed into $\mathbb{R}$.

+Its reciprocal function is the sigmoid ($\frac{1}{1 + e^{-x}}$),

+a central concept in *Deep Learning*.

+

+It should be noted that probabilities are not observed; what is observed is the binary

+*outcome* (0/1). This leads to two different perspectives on logistic regression:

+

+* In econometrics, interest lies in the latent model that determines the choice of

+the outcome. For example, if observing the choice to participate in the labor market,

+the goal is to model the factors determining this choice;

+* In *Machine Learning*, the latent model is only necessary to classify

+observations into the correct category.

+

+Parameter estimation for $\beta$ can be performed using maximum likelihood

+or regression, both of which are equivalent under certain assumptions.

+:::

+

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

::: {.note}

@@ -352,12 +546,27 @@ si l'objectif n'est pas de faire de la prédiction.

:::

+::::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+

+::: {.note}

+

+By default, `scikit` applies regularization to penalize non-parsimonious models (a behavior different from that of `statsmodels`). This default behavior should be kept in mind if the objective is not prediction.

+

+:::

+

+::::

+

+

```{python}

# packages utiles

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

import sklearn.metrics

```

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+

::: {.exercise}

## Exercice 2a : Régression logistique avec scikit

@@ -371,13 +580,35 @@ une mesure de qualité du modèle.

:::

+::::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+

+::: {.exercise}

+## Exercise 2a: Logistic Regression with scikit

+

+Using `scikit` with training and test samples:

+

+1. Evaluate the effect of the already-used variables on the probability of Republicans winning. Display the values of the coefficients.

+2. Derive a confusion matrix and a measure of model quality.

+3. Remove regularization using the `penalty` parameter. What effect does this have on the estimated parameters?

+

+:::

+

+::::

+

+

```{python}

#| output: false

#1. Modèle logit avec les mêmes variables que précédemment

-xvars = ['Unemployment_rate_2019', 'Median_Household_Income_2019', 'Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19', "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"]

+xvars = [

+ 'Unemployment_rate_2019', 'Median_Household_Income_2019',

+ 'Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19',

+ "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"

+]

-df2 = votes[["per_gop"] + xvars].copy()

+df2 = votes.loc[:, ["per_gop"] + xvars].copy()

df2['log_income'] = np.log(df2["Median_Household_Income_2019"])

df2 = df2.dropna().astype(np.float64)

@@ -437,6 +668,8 @@ from scipy import stats

```

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+

::: {.exercise}

## Exercice 2b : Régression logistique avec statmodels

@@ -445,6 +678,22 @@ En utilisant échantillons d'apprentissage et d'estimation :

1. Evaluer l'effet des variables déjà utilisées sur la probabilité des Républicains

de gagner.

2. Faire un test de ratio de vraisemblance concernant l'inclusion de la variable de (log)-revenu.

+:::

+

+::::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+

+::: {.exercise}

+## Exercise 2b: Logistic Regression with statsmodels

+

+Using training and test samples:

+

+1. Evaluate the effect of the already-used variables on the probability of Republicans winning.

+2. Perform a likelihood ratio test regarding the inclusion of the (log)-income variable.

+:::

+

+::::

```{python}

@@ -482,16 +731,21 @@ lr = -2*(mylogit.llf - logit_h0.llf)

lrdf = (logit_h0.df_resid - mylogit.df_resid)

lr_pvalue = stats.chi2.sf(lr, df=lrdf)

-#print(lr_pvalue)

-

-# La pvalue du test de maximum de ratio

-# de vraisemblance étant proche de 1,

-# cela signifie que la variable log revenu ajoute,

-# presque à coup sûr, de l'information au modèle.

+lr_pvalue

```

-:::

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+La p-value du test de maximum de ratio de vraisemblance étant proche de 1, cela signifie que la variable log revenu ajoute,

+presque à coup sûr, de l'information au modèle.

+::::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+The p-value of the likelihood ratio test being close to 1 means that the log-income variable almost certainly adds information to the model.

+::::

+

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

::: {.tip}

@@ -502,6 +756,23 @@ $$

:::

+::::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+

+::: {.tip}

+

+The test statistic is:

+$$

+LR = -2\log\bigg(\frac{\mathcal{L}_{\theta}}{\mathcal{L}_{\theta_0}}\bigg) = -2(\mathcal{l}_{\theta} - \mathcal{l}_{\theta_0})

+$$

+

+:::

+

+::::

+

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

# Pour aller plus loin

Ce chapitre n'évoque les enjeux de la régression

@@ -512,7 +783,7 @@ Dans le domaine du _machine learning_, les principales voies d'approfondissement

- Les modèles de régression alternatifs comme les forêts

aléatoires.

-- Les méthodes de _bootsting_ et _bagging_ pour découvrir la manière dont plusieurs modèles peuvent être entraînés de manière conjointe et leur prédiction sélectionnée selon un principe démocratique pour converger vers une meilleur décision qu'un modèle simple.

+- Les méthodes de _boosting_ et _bagging_ pour découvrir la manière dont plusieurs modèles peuvent être entraînés de manière conjointe et leur prédiction sélectionnée selon un principe démocratique pour converger vers une meilleure décision qu'un modèle simple.

- Les enjeux liés à l'explicabilité des modèles, un champ de recherche très actif, pour mieux comprendre les critères de décision des modèles.

Dans le domaine de l'économétrie, les principales voies d'approfondissement sont les suivantes:

@@ -523,5 +794,25 @@ jusqu'à présent ;

- Les tests d'hypothèses pour aller plus loin sur ces questions que notre

test de ratio de vraisemblance.

+## Références {.unnumbered}

+::::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+# Going Further

+

+This chapter only introduces the concepts of regression in a very introductory way. To expand on this, it is recommended to explore further based on your interests and needs.

+

+In the field of _machine learning_, the main areas for deeper exploration are:

+

+- Alternative regression models like random forests.

+- _Boosting_ and _bagging_ methods to learn how multiple models can be trained jointly and their predictions combined democratically to converge on better decisions than a single model.

+- Issues related to model explainability, a very active research area, to better understand the decision criteria of models.

+

+In the field of econometrics, the main areas for deeper exploration are:

+

+- Generalized linear models to explore regression with more general assumptions than those we have made so far;

+- Hypothesis testing to delve deeper into these questions beyond our likelihood ratio test.

+

+## References {.unnumbered}

-## Références {.unnumbered}

\ No newline at end of file

+::::

diff --git a/content/modelisation/4_featureselection.qmd b/content/modelisation/4_featureselection.qmd

index 3bfce9e7c6..344b3f90c6 100644

--- a/content/modelisation/4_featureselection.qmd

+++ b/content/modelisation/4_featureselection.qmd

@@ -1,19 +1,13 @@

---

title: "Sélection de variables : une introduction"

+title-en: "Variable selection: an introduction"

categories:

- Modélisation

- Exercice

description: |

- L'accès à des bases de données de plus en plus riches permet

- des modélisations de plus en plus raffinées. Cependant,

- les modèles parcimonieux sont généralement préférables

- aux modèles extrêmement riches pour obtenir de bonnes

- performances sur un nouveau jeu de données (prédictions

- _out-of-sample_). Les méthodes de sélection de variables,

- notamment le [`LASSO`](https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lasso_(statistiques)),

- permettent de sélectionner le signal le plus

- pertinent dilué au milieu du bruit lorsqu'on a beaucoup d'information à

- traiter.

+ L'accès à des bases de données de plus en plus riches permet des modélisations de plus en plus raffinées. Cependant, les modèles parcimonieux sont généralement préférables aux modèles extrêmement riches pour obtenir de bonnes performances sur un nouveau jeu de données (prédictions _out-of-sample_). Les méthodes de sélection de variables, notamment le [`LASSO`](https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lasso_(statistiques)), permettent de sélectionner le signal le plus pertinent dilué au milieu du bruit lorsqu'on a beaucoup d'information à traiter.

+description-en:

+ Access to ever-richer databases enables increasingly refined modeling. However, parsimonious models are generally preferable to extremely rich models for obtaining good performance on a new dataset (_out-of-sample_ predictions). Variable selection methods, such as [`LASSO`](https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lasso_(statistics)), can be used to select the most relevant signal diluted amidst the noise when there is a lot of information to process.

image: featured_selection.png

echo: false

---

@@ -24,11 +18,10 @@ echo: false

>}}

-

-

{{< include _import_data_ml.qmd >}}

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

Jusqu'à présent, nous avons supposé que les variables utiles à la prévision du

vote Républicain étaient connues du modélisateur. Nous n'avons ainsi exploité qu'une partie

limitée des variables disponibles dans nos données. Néanmoins, outre le fléau

@@ -51,6 +44,25 @@ de variables par le biais du LASSO.

Nous allons utiliser par la suite les fonctions ou

packages suivants :

+::::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+So far, we have assumed that the variables useful for predicting the Republican

+vote were known to the modeler. Thus, we have only used a limited portion of the

+available variables in our data. However, beyond the computational burden of building

+a model with a large number of variables, choosing a limited number of variables

+(a parsimonious model) reduces the risk of overfitting.

+

+How, then, can we choose the right number of variables and the best combination of these variables? There are multiple methods, including:

+

+* Relying on statistical performance criteria that penalize non-parsimonious models. For example, BIC.

+* *Backward elimination* techniques.

+* Building models where the statistic of interest penalizes the lack of parsimony (which is what we aim to do here).

+

+In this chapter, we will present the main challenges of variable selection through LASSO.

+

+We will subsequently use the following functions or packages:

+::::

```{python}

#| echo: true

@@ -70,12 +82,14 @@ import seaborn as sns

```

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+

# Principe du LASSO

## Principe général

La classe des modèles de *feature selection* est ainsi très vaste et regroupe

-un ensemble très diverse de modèles. Nous allons nous focaliser sur le LASSO

+un ensemble très divers de modèles. Nous allons nous focaliser sur le LASSO

(*Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator*)

qui est une extension de la régression linéaire qui vise à sélectionner des

modèles *sparses*. Ce type de modèle est central dans le champ du

@@ -83,7 +97,7 @@ modèles *sparses*. Ce type de modèle est central dans le champ du

de *L1-regularization* que de LASSO). Le LASSO est un cas particulier des

régressions elastic-net dont un autre cas fameux est la régression *ridge*.

Contrairement à la régression linéaire classique, elles fonctionnent également

-dans un cadre où $p>N$, c'est à dire où le nombre de régresseurs est très grand puisque supérieur

+dans un cadre où $p>N$, c'est-à-dire où le nombre de régresseurs est très grand puisque supérieur

au nombre d'observations.

## Pénalisation

@@ -95,7 +109,7 @@ Les variables dont la norme est non nulle passent ainsi le test de sélection.

::: {.tip}

Le LASSO est un programme d'optimisation sous contrainte. On cherche à trouver l'estimateur $\beta$ qui minimise l'erreur quadratique (régression linéaire) sous une contrainte additionnelle régularisant les paramètres:

$$

-\min_{\beta} \frac{1}{2}\mathbb{E}\bigg( \big( X\beta - y \big)^2 \bigg) \\

+\min_{\beta} \frac{1}{2}\mathbb{E}\bigg( \big( X\beta - y \big)^2 \bigg) \\

\text{s.t. } \sum_{j=1}^p |\beta_j| \leq t

$$

@@ -107,15 +121,69 @@ $$

où $\lambda$ est une réécriture de la régularisation précédente qui dépend de $\alpha$. La force de la pénalité appliquée aux modèles non parcimonieux dépend de ce paramètre.

+:::

+

+::::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+# The Principle of LASSO

+

+## General Principle

+

+The class of *feature selection* models is very broad and includes

+a diverse range of models. We will focus on LASSO

+(*Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator*),

+which is an extension of linear regression aimed at selecting

+*sparse* models. This type of model is central to the field of

+*Compressed sensing* (where the term *L1-regularization* is more commonly used than LASSO). LASSO is a special case of

+elastic-net regressions, with another famous case being *ridge regression*.

+Unlike classical linear regression, these methods also work

+in a framework where $p>N$, i.e., where the number of predictors is much larger than

+the number of observations.

+

+## Regularization

+

+By adopting the principle of a penalized objective function,

+LASSO allows certain coefficients to be set to 0.

+Variables with non-zero norms thus pass the selection test.

+

+::: {.tip}

+LASSO is a constrained optimization problem. It seeks to find the estimator $\beta$ that minimizes the quadratic error (linear regression) under an additional constraint regularizing the parameters:

+$$

+\min_{\beta} \frac{1}{2}\mathbb{E}\bigg( \big( X\beta - y \big)^2 \bigg) \\

+\text{s.t. } \sum_{j=1}^p |\beta_j| \leq t

+$$

+

+This program is reformulated using the Lagrangian, allowing for a more tractable minimization program:

+

+$$

+\beta^{\text{LASSO}} = \arg \min_{\beta} \frac{1}{2}\mathbb{E}\bigg( \big( X\beta - y \big)^2 \bigg) + \alpha \sum_{j=1}^p |\beta_j| = \arg \min_{\beta} ||y-X\beta||_{2}^{2} + \lambda ||\beta||_1

+$$

+

+where $\lambda$ is a reformulation of the previous regularization term, depending on $\alpha$. The strength of the penalty applied to non-parsimonious models depends on this parameter.

:::

+::::

+

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

## Première régression LASSO

Comme nous cherchons à trouver les

meilleurs prédicteurs du vote Républicain,

nous allons retirer les variables

-qui sont dérivables directement de celles-ci: les scores des concurrents !

+qui sont dérivables directement de celles-ci : les scores des concurrents !

+::::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+## First LASSO Regression

+

+As we aim to find the

+best predictors of the Republican vote,

+we will remove variables

+that can be directly derived from these: the competitors' scores!

+::::

```{python}

@@ -134,10 +202,20 @@ df2 = df2.loc[

df2 = df2.loc[:,~df2.columns.duplicated()]

```

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

Dans cet exercice, nous utiliserons

également une fonction pour extraire

les variables sélectionnées par le LASSO,

-la voici

+la voici :

+::::

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+In this exercise, we will also use

+a function to extract

+the variables selected by LASSO,

+here it is:

+::::

+

```{python}

#| echo: true

@@ -183,6 +261,8 @@ def extract_features_selected(lasso: Pipeline, preprocessing_step_name: str = 'p

return features_selec

```

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+

::: {.exercise}

## Exercice 1 : Premier LASSO

@@ -209,11 +289,11 @@ catégorielles.

En supposant que votre _pipeline_ soit dans un objet nommé `pipeline` et que la dernière étape

est nommée `model`, vous pouvez

-directement accéder à cette étape en utilisant l'objet `pipeline['model']`

+directement accéder à cette étape en utilisant l'objet `pipeline['model']`.

5. Afficher les valeurs des coefficients. Quelles variables ont une valeur non nulle ?

-4. Montrer que les variables sélectionnées sont parfois très corrélées.

-5. Comparer la performance de ce modèle parcimonieux avec celle d'un modèle avec plus de variables

+6. Montrer que les variables sélectionnées sont parfois très corrélées.

+7. Comparer la performance de ce modèle parcimonieux avec celle d'un modèle avec plus de variables.

```

-Lorsque des observations sont linéairement séparables,

-il existe une infinité de frontières de décision linéaire séparant les deux classes. Le _"meilleur"_ choix est de prendre la marge maximale permettant de séparer les données. La distance entre les deux marges est $\frac{2}{||\theta||}$. Donc maximiser cette distance entre deux hyperplans revient à minimiser $||\theta||^2$ sous la contrainte $y_i(\theta^Tx_i + b) \geq 1$.

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+Lorsque des observations sont linéairement séparables, il existe une infinité de frontières de décision linéaire séparant les deux classes. Le _"meilleur"_ choix est de prendre la marge maximale permettant de séparer les données. La distance entre les deux marges est $\frac{2}{||\theta||}$. Donc maximiser cette distance entre deux hyperplans revient à minimiser $||\theta||^2$ sous la contrainte $y_i(\theta^Tx_i + b) \geq 1$.

Dans le cas non linéairement séparable, la *hinge loss* $\max\big(0,y_i(\theta^Tx_i + b)\big)$ permet de linéariser la fonction de perte, ce qui donne le programme d'optimisation suivant :

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+When observations are linearly separable, there is an infinite number of linear decision boundaries separating the two classes. The _"best"_ choice is to select the maximum margin that separates the data. The distance between the two margins is $\frac{2}{||\theta||}$. Thus, maximizing this distance between two hyperplanes is equivalent to minimizing $||\theta||^2$ under the constraint $y_i(\theta^Tx_i + b) \geq 1$.

+

+In the non-linearly separable case, the *hinge loss* $\max\big(0,y_i(\theta^Tx_i + b)\big)$ allows for linearizing the loss function, resulting in the following optimization problem:

+:::

$$

\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \max\big(0,y_i(\theta^Tx_i + b)\big) + \lambda ||\theta||^2

$$

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

La généralisation au cas non linéaire implique d'introduire des noyaux transformant l'espace de coordonnées des observations.

+:::

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+Generalization to the non-linear case involves introducing kernels that transform the coordinate space of the observations.

:::

+::::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

# Application

Pour appliquer un modèle de classification, il nous faut

@@ -101,6 +161,16 @@ défaite d'un des partis.

Même si les Républicains ont perdu en 2020, ils l'ont emporté

dans plus de comtés (moins peuplés). Nous allons considérer

que la victoire des Républicains est notre _label_ 1 et la défaite _0_.

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+# Application

+

+To apply a classification model, we need to find a dichotomous variable. The natural choice is to use the dichotomous variable of a party's victory or defeat.

+

+Even though the Republicans lost in 2020, they won in more counties (less populated ones). We will consider a Republican victory as our _label_ 1 and a defeat as _0_.

+:::

+

```{python}

#| echo: true

@@ -111,7 +181,10 @@ from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

```

-::: {.exercise}

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+

+:::: {.exercise}

## Exercice 1 : Premier algorithme de classification

1. Créer une variable *dummy* appelée `y` dont la valeur vaut 1 quand les républicains l'emportent.

@@ -133,7 +206,48 @@ créer des échantillons de test (20 % des observations) et d'estimation (80 %)

6. Changer de variables *x*. Utiliser uniquement le résultat passé du vote démocrate (année 2016) et le revenu. Les variables en question sont `share_2016_republican` et `Median_Household_Income_2019`. Regarder les résultats, notamment la matrice de confusion.

7. [OPTIONNEL] Faire une 5-fold validation croisée pour déterminer le paramètre *C* idéal.

+::::

+

+:::

+

+

+:::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+::: {.exercise}

+

+## Exercise 1: First classification algorithm

+

+1. Create a *dummy* variable called `y` with a value of 1 when the Republicans win.

+2. Using the ready-to-use function `train_test_split` from the `sklearn.model_selection` library,

+create test samples (20% of the observations) and training samples (80%) with the following *features*:

+

+```python

+vars = [

+ "Unemployment_rate_2019", "Median_Household_Income_2019",

+ "Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19",

+ "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"

+]

+```

+

+and use the variable `y` as the *label*.

+

+*Note: You may encounter the following warning:*

+

+> A column-vector y was passed when a 1d array was expected. Please change the shape of y to (n_samples, ), for example using ravel()

+

+*Note: To avoid this warning every time you train your model, you can use `DataFrame[['y']].values.ravel()` instead of `DataFrame[['y']]` when preparing your samples.*

+

+3. Train an SVM classifier with a regularization parameter `C = 1`. Examine the following performance metrics: `accuracy`, `f1`, `recall`, and `precision`.

+

+4. Check the confusion matrix: despite seemingly reasonable scores, you should notice a significant issue.

+

+5. Repeat the previous steps using normalized variables. Are the results different?

+

+6. Change the *x* variables. Use only the previous Democratic vote result (2016) and income. The variables in question are `share_2016_republican` and `Median_Household_Income_2019`. Examine the results, particularly the confusion matrix.

+

+7. [OPTIONAL] Perform 5-fold cross-validation to determine the ideal *C* parameter.

+

:::

+::::

```{python}

@@ -144,7 +258,11 @@ votes['y'] = (votes['votes_gop'] > votes['votes_dem']).astype(int)

```{python}

#2. Création des échantillons d'entraînement et de validation

-xvars = ['Unemployment_rate_2019', 'Median_Household_Income_2019', 'Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19', "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"]

+xvars = [

+ 'Unemployment_rate_2019', 'Median_Household_Income_2019',

+ 'Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2015-19',

+ "Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2015-19"

+]

df = votes.loc[:, ["y"] + xvars]

@@ -154,13 +272,25 @@ X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

)

```

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

On obtient donc un ensemble de _features_ d'entraînement ayant cette forme:

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+We thus obtain a set of training _features_ with the following structure:

+:::

```{python}

X_train.head()

```

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

Et les _labels_ associés sont les suivants:

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+And the associated _labels_ are as follows:

+:::

```{python}

y_test

@@ -179,11 +309,22 @@ sc_precision = sklearn.metrics.precision_score(y_pred, y_test)

```

```{python}

-stats_perf = pd.DataFrame.from_dict({"Accuracy": [sc_accuracy], "Recall": [sc_recall],

- "Precision": [sc_precision], "F1": [sc_f1]}, orient = "index", columns = ["Score"])

+stats_perf = pd.DataFrame.from_dict(

+ {

+ "Accuracy": [sc_accuracy], "Recall": [sc_recall],

+ "Precision": [sc_precision], "F1": [sc_f1]

+ }, orient = "index", columns = ["Score"]

+)

```

-A l'issue de la question 3, notre classifieur manque totalement les labels 0, qui sont minoritaires. Parmi les raisons possibles: l'échelle des variables. Le revenu, notamment, a une distribution qui peut écraser celle des autres variables, dans un modèle linéaire. Il faut donc, a minima, standardiser les variables, ce qui est l'objet de la question 4

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+A l'issue de la question 3, notre classifieur manque totalement les labels 0, qui sont minoritaires. Parmi les raisons possibles : l'échelle des variables. Le revenu, notamment, a une distribution qui peut écraser celle des autres variables, dans un modèle linéaire. Il faut donc, a minima, standardiser les variables, ce qui est l'objet de la question 4.

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+At the end of question 3, our classifier completely misses the 0 labels, which are in the minority. One possible reason is the scale of the variables. Income, in particular, has a distribution that can dominate the others in a linear model. Therefore, at a minimum, it is necessary to standardize the variables, which is the focus of question 4.

+:::

@@ -201,15 +342,21 @@ disp.plot()

plt.show()

```

-Standardiser les variables n'apporte finalement pas de gain:

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+Standardiser les variables n'apporte finalement pas de gain :

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+Standardizing the variables ultimately does not bring any improvement:

+:::

```{python}

import sklearn.preprocessing as preprocessing

X = df.loc[:, xvars]

y = df[['y']]

-scaler = preprocessing.StandardScaler().fit(X) #Ici on estime

-X = scaler.transform(X) #Ici on standardise

+scaler = preprocessing.StandardScaler().fit(X)

+X = scaler.transform(X)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X,

@@ -220,30 +367,39 @@ clf = svm.SVC(kernel='linear', C=1).fit(X_train, y_train)

predictions = clf.predict(X_test)

cm = sklearn.metrics.confusion_matrix(y_test, predictions, labels=clf.classes_)

disp = sklearn.metrics.ConfusionMatrixDisplay(

- confusion_matrix=cm,

- display_labels=clf.classes_

- )

+ confusion_matrix=cm,

+ display_labels=clf.classes_

+)

disp.plot()

plt.show()

```

-Il faut donc aller plus loin : le problème ne vient pas de l'échelle mais du choix des variables. C'est pour cette raison que l'étape de sélection de variable est cruciale et qu'un chapitre y est consacré.

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

+Il faut donc aller plus loin : le problème ne vient pas de l'échelle mais du choix des variables. C'est pour cette raison que l'étape de sélection de variables est cruciale et qu'un chapitre y est consacré.

-A l'issue de la question 6,

-le nouveau classifieur avec devrait avoir les performances suivantes :

+À l'issue de la question 6, le nouveau classifieur devrait avoir les performances suivantes :

+:::

-```{python}

-#| output: asis

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+It is therefore necessary to go further: the problem does not lie in the scale but in the choice of variables. This is why the step of variable selection is crucial and why a chapter is dedicated to it.

-out = pd.DataFrame.from_dict({"Accuracy": [sc_accuracy], "Recall": [sc_recall],

- "Precision": [sc_precision], "F1": [sc_f1]}, orient = "index", columns = ["Score"])

-```

+At the end of question 6, the new classifier should have the following performance:

+:::

+```{python}

+#| output: asis

+out = pd.DataFrame.from_dict(

+ {

+ "Accuracy": [sc_accuracy], "Recall": [sc_recall],

+ "Precision": [sc_precision], "F1": [sc_f1]

+ }, orient = "index", columns = ["Score"]

+)

+```

```{python}

-# 6. Refaire les questions en changeant la variable X.

+# Question 6

votes['y'] = (votes['votes_gop'] > votes['votes_dem']).astype(int)

df = votes[["y", "share_2016_republican", 'Median_Household_Income_2019']]

tempdf = df.dropna(how = "any")

@@ -266,11 +422,6 @@ sc_f1 = sklearn.metrics.f1_score(y_pred, y_test)

sc_recall = sklearn.metrics.recall_score(y_pred, y_test)

sc_precision = sklearn.metrics.precision_score(y_pred, y_test)

-#print(sc_accuracy)

-#print(sc_f1)

-#print(sc_recall)

-#print(sc_precision)

-

predictions = clf.predict(X_test)

cm = sklearn.metrics.confusion_matrix(y_test, predictions, labels=clf.classes_)

disp = sklearn.metrics.ConfusionMatrixDisplay(

@@ -278,7 +429,6 @@ disp = sklearn.metrics.ConfusionMatrixDisplay(

display_labels=clf.classes_

)

disp.plot()

-# On obtient un résultat beaucoup plus cohérent.

plt.savefig("confusion_matrix3.png")

```

diff --git a/content/modelisation/3_regression.qmd b/content/modelisation/3_regression.qmd

index ceaada2199..21ffc2f2de 100644

--- a/content/modelisation/3_regression.qmd

+++ b/content/modelisation/3_regression.qmd

@@ -1,14 +1,12 @@

---

title: "Introduction à la régression"

+title-en: "An introduction to regression"

categories:

- Modélisation

description: |

- La régression linéaire est la première modélisation statistique

- qu'on découvre dans un cursus quantitatif. Il s'agit en effet d'une

- méthode très intuitive et très riche. Le _Machine Learning_ permet de

- l'appréhender d'une autre manière que l'économétrie. Avec `scikit` et

- `statsmodels`, on dispose de tous les outils pour satisfaire à la fois

- data scientists et économistes.

+ La régression linéaire est la première modélisation statistique qu'on découvre dans un cursus quantitatif. Il s'agit en effet d'une méthode très intuitive et très riche. Le _Machine Learning_ permet de l'appréhender d'une autre manière que l'économétrie. Avec `scikit` et `statsmodels`, on dispose de tous les outils pour satisfaire à la fois data scientists et économistes.

+description-en: |

+ Linear regression is the first statistical modeling to be discovered in a quantitative curriculum. It is a very intuitive and rich method. Machine Learning allows us to approach it in a different way to econometrics. With `scikit` and `statsmodels`, we have all the tools we need to satisfy both data scientists and economists.

image: featured_regression.png

echo: false

bibliography: ../../reference.bib

@@ -19,6 +17,7 @@ bibliography: ../../reference.bib

>}}

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="fr"}

Le précédent chapitre visait à proposer un premier modèle pour comprendre

les comtés où le parti Républicain l'emporte. La variable d'intérêt étant

bimodale (victoire ou défaite), on était dans le cadre d'un modèle de

@@ -28,13 +27,29 @@ Maintenant, sur les mêmes données, on va proposer un modèle de régression

pour expliquer le score du parti Républicain. La variable est donc continue.

Nous ignorerons le fait que ses bornes se trouvent entre 0 et 100 et donc

qu'il faudrait, pour être rigoureux, transformer l'échelle afin d'avoir

-des données dans cet intervalle.

+des données dans cet intervalle.

+:::

+

+::: {.content-visible when-profile="en"}

+The previous chapter aimed to propose a first model to understand the counties where the Republican Party wins. The variable of interest was bimodal (win or lose), placing us within the framework of a classification model.

+

+Now, using the same data, we will propose a regression model to explain the Republican Party's score. The variable is thus continuous. We will ignore the fact that its bounds lie between 0 and 100, meaning that to be rigorous, we would need to transform the scale so that the data fits within this interval.

+:::

+